Reenchantment in Restoration

Madeleine Young

→BFA FD 2023

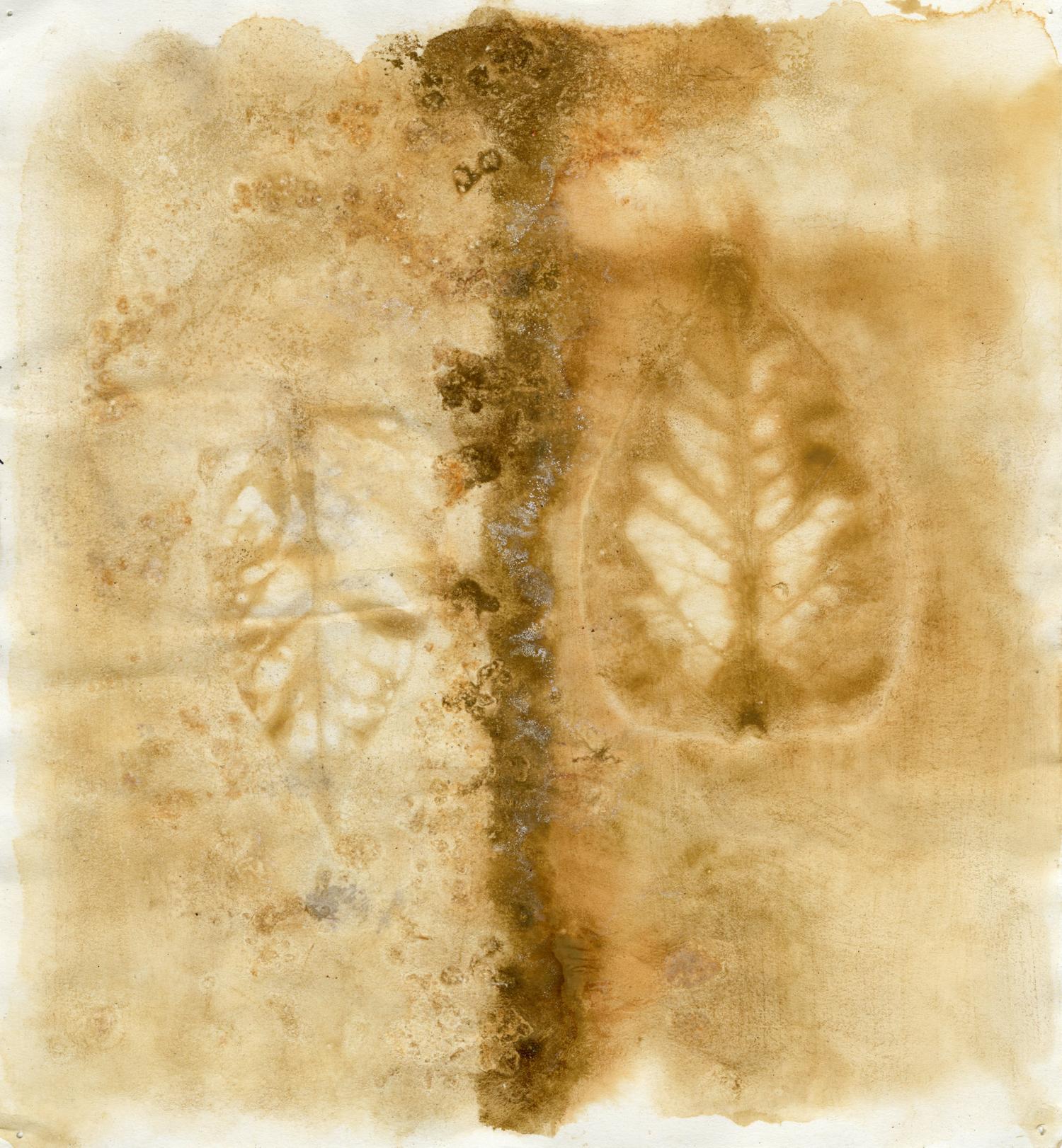

Images by the author.

ONE.

The Blackstone River’s richness caused it to be coveted by early industries along the eastern coast of what is now called America. Along the banks of the river, dams and towns and cities sprung up in support of the burgeoning mills and factories; the construction of the Blackstone Canal was heralded as the beginning of a new age of growth and prosperity. Today, walking along the muddy edge of the canal, it’s hard to imagine that it once drew so much hope to the river.

The industry and its supporting infrastructure have disappeared, leaving behind a legacy of pollutants and disturbance. Building up the Blackstone compartmentalized the land; the divisions of farm, factory, wilderness, and living space were made undeniably visible. Transportation along the canal was tied to trade, while the river’s current was transformed into pure power. The former strings of entanglement were severed by human hands, disassembled, and then re-tied to fit the needs of capital and industry; by reforming the landscape, its parts became alienated from their relationships. Though the manufacturing and textiles industries soon moved out of New England, these re-assemblages remained intact.

Inland 40 miles, before the water runs into the Narragansett Bay, Fisherville Mill stood on Main St. in Grafton, Massachusetts. Once, it manufactured textiles, tool and die, lawn furniture and steel products, as well as foam rubber. Contaminants held within the mill were leached into the water in 1999, when a fire destroyed the building. Now the mill’s plot is hidden behind a barbed wire fence and a steep bank, overgrown with bittersweet vines and tall grass. Across the street from where it operated is the Mill Villages Park, nested in between the river and the canal, but the remnants of the mill remain visible.

TWO.

Moreover, there is an implication that without direct intervention the ecosystem would die, much like a sick patient without medical care. But promoting the “health” of one ecosystem might mean killing another that exists in between.

The introduction of non-native species, some of which persisted and overwhelmed the ecosystem, disturbed the ecological profile of the Blackstone. In many restoration efforts, non-native plants and invasives are often framed as the greatest ecological threat. The language used to describe these plants is violent—words such as “killer,” “threat,” and “plague”and a line is drawn between the site’s false and true nature.

To say that the pretty-pretty purple loosestrife flower is a horrible threat to “real nature” breeds a cultural mistrust of the natural environment. Why are we identifying only death in an environment still so full of life? The alterations to the ecosystem are undeniable—trichloroethylene and crude oil persist in the water, in both the plant and animal life in and around where the Fisherville Mill stood—but this is not a two-sided war.

The system is not closed; there is not only one. The ecosystems are simultaneous, as they cross over and weave into each other, tie knots and then root down in place. There is still an abundance of life, even in a disturbed environment. In the case of the Fisherville Mill, there is damage, but that is not always the case. Disturbance is not at the end of the story, at the end of this world. Landscapes and their make-ups change over time, forever in flux with their own momentum and the internal and external forces. The Blackstone River was on a fluctuating path before human activity existed along its banks. There have been worlds and worlds before this one now, the disturbances that have happened and continue to happen are invitations for new formations of relationships and transforming perspectives. What is exciting is what might occur through this open door. We are forever being disturbed, forever in the middle of the story, forever at the turn of the next page.

THREE.

Cindy Goulder’s poem “Volunteer Revegetation Saturday” introduces a peculiar word: disengardening. She writes, “If it is the path that makes the garden, and then the garden that civilizes the wild, then we are disengardening now.” This is the opposite of gardening, but it is not re-making wild, as the wilderness is not made. Disengarden-ing still involves itself with the world but not through means of control or cultivation; to disengarden is to move with the landscape, not over it. This is not glamorous, and there will be no trophy or sunset moment at the end where we look back and sigh proudly at it all, pristine because it was tended by our benevolent hands. This is disengardening.

While we disengarden the landscape, we might also begin to become re-enchanted in it. Enchantment is derived from the French word chanter: to sing. It is a casting of spells, of pleasure and delight and awe. Its prefix re- has two definitions. First, an indication of a “going back” or backwarding. This is not the definition concerned with reenchantment. This “re” implies that magic does not exist currently, or that it once did. Yet magic can still exist in this today! We do not need to leave the present to find it. This specific “re,” is a second definition, is a repetition, an “again.” Reenchantment of the landscape does not consist of a perfect return to “back then.” Perhaps it is a rapid hurtling towards magic soon.

There is still magic in the weeds and under the dead roots. There is still a river running, the parts of its make up are still present in some ways. Fisherville Mill and the Mill Villages Park are in the wake of a disturbance and the repetition of a creation. The ongoing life at this site is casting spells. The life that persists there is inviting hands to join in its persistence, to slowly and steadily sing and build up a new world, tell a new story, again and again, and again, and again.

Madeleine Young, a maker from Toronto, Canada, is less focused than last season but maybe more silly.